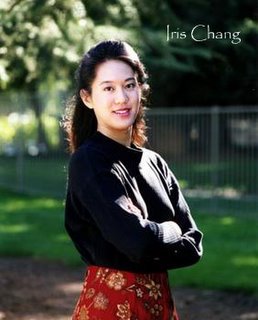

Iris Chang One Year Later...

As a little girl, Iris Chang went to her school library looking for a book about the Chinese city of

Iris’ parents who had relayed the story could be described as intellectuals that immigrated to the

But on that day at the library somewhere around 30 years ago, Iris found no book about

One year ago on November 9, 2004, Iris Chang, the beautiful, gracefully articulate, now 36-year old historian and best-selling author drove her 1999 Oldsmobile Alero alone in the dead of night just east of San Jose, California headed west on Highway 17. She had slipped out of bed some time in the early morning, leaving her husband of thirteen years Brett Douglass, an engineer at Cisco Systems, asleep in their

It appears that she simply drove for a while – probably less than 30 minutes -- until it seemed that she was “far enough” away. She pulled off the highway onto what was described as a steep utility road and parked. At that time it may have still been dark. The details of exactly how things happened after that are excruciating to imagine.

She had brought with her a large-sized handgun in a cardboard box on the passenger’s seat. She had secretly purchased the Civil War era “relic” the day before at an antique shop. Antique guns have no waiting period for purchase in

At sometime that morning probably just around sunrise, she loaded a bullet into each chamber of the gun and placed the barrel upward inside her mouth. In an instant Iris Chang died alone inside her car on a dusty turnoff near the Lexington Reservoir, her head fell to rest against the driver’s side window. A passerby would find her about two hours later. In the back seat behind her there was child’s car seat with a teddy bear toy.

The first accounts of a young author my age committing suicide – who had written an important historical account (of which I knew nothing), was a suddenly a bit arresting. I decided to do a quick Internet search on this new name “Iris Chang.”

On Google, lots of things popped up – her three books, interviews, even a few audio interviews on public radio. I remember this story suddenly felt eerie, and I quickly realized that an immense tragedy had just occurred.

Iris had contributed immensely to the cause of history – in particular, her second book, published in 1997 before she was thirty, was perhaps one of the most controversial and important of the entire decade.

“The Rape of Nanking” shed light on a forgotten tragedy. The scope of this tragedy, Iris had discovered long after that day in the library as a little girl, was huge – so huge, it put an entirely new perspective on the Second World War. In fact, it turns out that there wasn’t just one holocaust, there was another – and stunningly, this one seemed every bit as horrifying as the Jewish Holocaust.

Her book became the first comprehensive documentation of the

This was a woman of conviction, courage, intellect, talent and tremendous empathy for the suffering of others who was suddenly lost while a new mother and in the prime of her life. She had everything to live for. It felt like this was life at its cruelest.

-

The story of what happened in

When the Japanese Imperial Army invaded the then capital city of

Hundreds of thousands of innocent Chinese civilians would be tortured and killed in a matter of weeks. The numbers were very big, but the scope of it all wasn’t just about the numbers. In this single paragraph from the Introduction of The Rape of Nanking, the immensity of the horror becomes more clear as Iris begins her disparaging portrait of insane human barbarism:

The Rape of

In total, somewhere between 19 million to 36 million Chinese civilians were ultimately killed as a result of the invasion of China by Japan in WWII, a rather stunning statistic when you figure that six million is the commonly accepted number of Jews murdered by the Nazi’s during the same general period. The world’s collective amnesia about an event of this magnitude is simply inexplicable.

An important part of Iris Chang’s contribution was as a skilled researcher. Before The Rape of Nanking, some of the horrifying details were not well documented (barely documented at all in English), a factor contributing to the event’s obscurity. She had a tireless persistence to comb through archives (one story relays that she stayed in the library so late and concentrated so intently, she once found herself still inside a library after it had closed and the staff left). Another important ability was her fluency in Mandarin which allowed her to conduct interviews with survivors in

One discovery in particular made for a surprising twist to the story. Iris was able to contact the son of John Rabe, who was a Nazi living in

Iris located Rabe's granddaughter, Ursula Reihardt, who told Iris there was a diary. Later the diary was translated by publishers in English and Chinese. The diary turned out to have a plethora of corroborating evidence of atrocities and is considered a significant historical find. Iris relayed later that when she showed this diary to her father, he broke down in tears.

Iris also wrote in her book about Minnie Vautrin, an American running the Education Department and Dean of Studies at a college in

In a strangely familiar story, after Vautrin returned to the

-

Iris described in her book something she called the “Second Rape” or the “Rape of History.” Some Japanese groups, namely Japanese “Nationalist” groups had denied that the Rape of Nanking ever happened. Today, historians consider the events undisputed, and although her book caused something of an uproar among these groups, it seems that the facts have been accepted by scholars outside

According to Iris, it is against the law not to teach the history of the holocaust in German public schools, yet in Japan most of the details of WWII is are conveniently left out of the curriculum. She said:

Through it all she was unyielding in her view that Japan after 60 years of denial must make a clear and unequivocal apology. Once on the MacNeil-Lehrer News Hour when the Japanese ambassador spoke about

Helen Zia, author of “Asian-American Dreams: Emergence of an American People” said, "To see her on TV, defending the 'Rape of Nanking' so fiercely and so fearlessly -- I just sat down, stopped, in awe."

-

Iris spent her childhood in Champaign-Urbana eventually attending the

In the course of the next decade, she set out writing and discovering three very different stories – each related in some way to her Chinese heritage, but universally pertinent. In a broad sense they each tell true stories about people that were victims of governmental power … and she spent her life advocating justice and civil liberties for those that suffered cruelty at the hands of others. Iris had a profound gift for writing, but also a profound gift for finding true stories of particular relevance – untold stories that desperately needed a storyteller.

The Thread of the Silkworm, her first book, was published when she  was only 25. This is remarkable when you consider the technical subject matter (literally rocket science) that made up the background of the story, and the difficult and careful research she used to depict times, events and places accurately. Silkworm was a rather griping depiction of the life of Tsien hu-shen, the brilliant Cal Tec scientist who came to

was only 25. This is remarkable when you consider the technical subject matter (literally rocket science) that made up the background of the story, and the difficult and careful research she used to depict times, events and places accurately. Silkworm was a rather griping depiction of the life of Tsien hu-shen, the brilliant Cal Tec scientist who came to

The Rape of Nanking is the book for which Iris Chang will always be remembered. This was a breakthrough book, not only for Iris, but for history. Its scope and importance is hard to overstate. This depiction of an unbelievable WWII atrocity committed by the Japanese Imperial Army on the defenseless then-capital city of

The Chinese in America: A Narrative History, is a supremely interesting epic book published in 2003 depicting the history of

-

Along with the fame, the cause of bringing to light injustice, the controversy, Iris suffered the severe dark side of its painful past. At times researching

From this backdrop, something snapped in the summer of 2004 when Iris went to

Excerpts from her suicide note, of which she wrote three drafts, show that Iris had reached a breaking point of desperation, fear and guilt. She believed that someone was actively trying to discredit her and she was afraid for her safety. “I sensed suddenly threats to my own life,” she wrote, “an eerie feeling that I was being followed in the streets, the white van parked outside my house, damaged mail arriving at my P.O. Box.”

In a transgression of overwhelm and pain her note says, “Each breath is becoming difficult for me to take -- the anxiety can be compared to drowning in an open sea. I know that my actions will transfer some of this pain to others, indeed those who love me the most. Please forgive me. Forgive me because I cannot forgive myself.”

It’s probably too simplistic to say that her depression and death was caused solely by her work, but clearly they played a major role. She had tendency to profoundly empathize with victims, and her work seemed to define and engulf her.

Aside from attention her death drew back to her work, her illness also shed light on the profoundly serious disease of depression. It brought into view the stigma of shame associated with mental illness, and the reluctance of victims to get the help they need. This problem, it has been suggested, may be particularly prevalent in the Asian culture.

-

At Chang’s memorial in

-

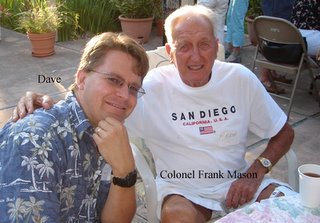

In the spring of this year I was fortunate enough to meet Dr.

In the spring of this year I was fortunate enough to meet Dr.

When he talks about

When he talks about

When he read about Iris’ death in the newspaper he was incredulous. His voice lowers when he recalls that day. “I just couldn’t believe it.” In pondering his voice cracks and its hard for him to say, “Her heart just gave out…”

-

Today, millions of people have heard of The Rape of Nanking, millions more than would have known without Iris Chang’s work. Still, only a small minority of Americans have any notion of what happened on that side of the world during the war.

Iris’ publisher and agent, Susan Rabiner said at Iris’ memorial: “Now, some child will go to the library and -- though there wasn't such a book for Iris when she was growing up -- there will be a book in a language they will understand. And they will see the photographs and see a beautiful young woman, completely devoted to her cause.“

In the end I run out of words to put down about Iris Chang, author, scholar, “change agent”, advocate, historian, teacher, mother. I often think that each time someone dies, the world becomes a different place. I’ve never felt that more than with Iris Chang. It feels unfair that I only learned about her and her cause a few hours after she was gone.

But Iris Chang leaves a big legacy, an indelible message … and she left a warning. In a 2004 Interview she said:

“Personally I believe we are living in more dangerous times then ever. Don’t forget we now have the technological capacity to exterminate the human race with nuclear weapons, so the stakes are much larger. I don’t think that human behavior has evolved much really beyond what it had been since caveman times. We have civilization but the veneer of that civilization is exceedingly thin. If anything I think that while there’s much more attempts to try to bring about peace, that the reality is that the numbers of people who’ve died during wars or being murdered by their own governments has increased because the technological means to perpetrate mass murder has increased, but basic human nature has stayed the same.”

“Every 80 years or so the world is going to be populated with entirely different people. During that 80 years there is going to be a ruthless struggle as the world’s power and capital is transferred from one set of hands to another. Every generation is going to have to confront these basic challenges to their civil liberties and civil rights, not just in the

Iris had something important to say, and it is immensely sad that she herself suffered so much while she tried to bring awareness and justice to the suffering of others. People like this are rare, and oh what misfortune that we are all powerless to change her demise.

Now that a year is passed, I can see that over time her memory will eventually fade much like the victims she herself hoped would never be forgotten. Others will pick up her causes, but there likely won’t be another like her. Please don’t forget this woman, the last victim of The Rape of Nanking.

One year later ... Iris, farewell.

Resources:

There are many resources about Iris on the net. Here are a few. Above all else, I recommend Glenn Zucman’s audio interview:

Best Audio Interview: Glenn Zucman's Interview With Chang - April 2004 This is an mp3 recording (Ipod compatible) of an Interview with Chang at the LA Times Festival of Books at UCLA for Glenn Zucman’s radio show called “Strange Angels.” This half hour Interview is perhaps one of the best concise audio interviews of Chang available. Iris discusses a wide range of topics including all three of her books. Zucman is also an artist – see Zucman’s portrait of Chang.

Other Audio Interviews:

Audio Interview: Neal Conan Interviews Iris Chang on NPR about The Chinese in America May 7, 2003

Audio Interview: NPR Interview of Chang on “All Things Considered” December 3, 1997

Audio Interview: Penny Nelson Interview Iris Chang on “Forum” June 23, 2003

Audio Interview: Interview of Chang on the Paula Gordon Show April 22, 2004

Other Video: A good video of Chang at The Committee of 100 - 2003 and The Video.

Another article by Benson written

Mourning Iris Chang by Dr. William Y. Jiang (pdf file)

Memorial site – lots of pictures

San Francisco Chronicle article by Laurie Barkin: Unbearable sadness of others' pain

1998 Article about response to The Rape of Nanking: When Iris Chang wrote ``The Rape of Nanking,'' to memorialize one of the bloodiest massacres of civilians in modern times, she wasn't prepared for the firestorm she started

Metro Active Article by Ami Chen Mills: Breaking the Silence

The Iris Chang Scholarship Fund

Attn: Jeff Roley